There are certain places in Wales where it is possible to find oneself at the beginning of things. The Edeirnion Valley is one of those places - it stretches so far back in our history that one is apt to squint at the distance. And much of Edeirnion’s long history seems to somehow coalesce at this coming together place of rivers and route ways, eventually firming to become the ancient town of Corwen.

What beginnings then, may you find here? There are many. At the church of St Mael & St Sulien you may reasonably claim to find yourself at the dawn of Christianity in these Islands, for here was the site of a clas, a mother church, a sacred space of immense importance in the early organisation of the Christian church. There are others, of course - Corwen is not alone. Abergele, Bangor Is-coed (Bangor on Dee), Llanarmon-yn-Iâl, Llanynys and St Asaph were thought to be clasau all,(1) and there are places older still, such as Dyserth and Llangollen, sites of saints' cells and hermitages. But Corwen has such dizzying depths, and there are hints here of an older, pre-Conquest Christian faith and older evidence that would suggest that its ancient age was perhaps a reason for the building of the church, here by the sacred Dee.

The church is so full of wonders and mysteries, they could fairly blister the eyes. It is a challenge to know where to begin in fathoming its depths. The church as it stands today is certainly early medieval, twelfth century, its clas foundation evidenced in its cruciform design - with nave, chancel, north and south transepts. It appears in both the Norwich Taxation of 1254 and the Taxatio of Pope Nicholas of 1291 as Ecclesia de Corvaen.

Looking towards the altar and the reset medieval lancet windows.

It would seem to have originally been dedicated only to St Sulien, with no mention of St Mael in the 17th and 18th century works of Lhuyd and Browne Willis. Yet, the Reverend D. R. Thomas, writing in 1874 has the church dedicated to both Sulien and Mael, stating that they were ‘companion missionaries’,(2) while Baring-Gould and Fisher state that, ‘Mael is usually coupled with Sulien; maybe they were brothers.’(3) Both Sulien and Mael were Bretons by birth, who seem to have arrived in Wales in the company of St Cadfan and after much missionary work ended their days, amongst many thousands of other saints, at Ynys Enlli.(4) Both were active in Wales in the 6th century, which lends itself to the belief that Corwen was extremely important in the growth of Christianity in north Wales. When exactly Mael became attached to the church is not known, but it remains a curiosity that nearby Ffynnon Sulien is entirely shy of Mael. One wonders if later writers have not quietly inserted Mael into Sulien’s church at Corwen, thinking too right a perceived mistake. After all, Mael and Sulien can also be found as dedicants of the church at Cwm in Flintshire.

St Mael & St Sulien's viewed from the east - note the lancet windows which retain their medieval appearance far more than when viewed from the chancel.

If the form of the current church is largely 12th century, there are signs that the site was of Christian significance much earlier. The churchyard is now heptagonal, but was likely curvilinear - a good indication of an early medieval foundation. Within the much later re-built south doorway, behind a rusting metal grid, serving now as a lintel, is what the Royal Commission describes as,

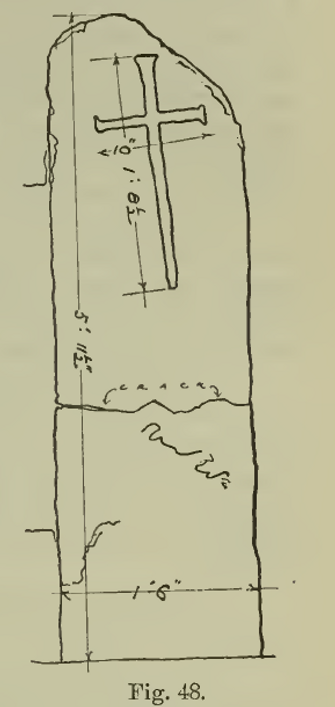

‘a rude stone on which is incised a cross, 21 inches in length, the long arm of which is narrowed downwards to a point, giving it an appearance of a dagger, a feature which has doubtless led to its being called ‘Owain Glyndwr’s dagger’’

The legend as told, is that the great man hurled his dagger from the vantage point of Pen y pigyn, in a rage some say, which struck a rock far below in the town, leaving its image in the stone. William Hutton, a Birmingham antiquarian and seemingly something of a wit, visited St Mael and St Sulien’s in 1803, and wrote of being shown the mark by a guide who told him,

‘with a face more serious than my own, that upon the Berwyn Mountain behind the Church, was a place called Glendwr’s Seat, from which he threw his dagger, and made the above impression upon the stone. If this had happened in our day, the whole bench of bishops would have united in pronouncing him a Jacobin...I climbed the mountain to what is called Owen’s Seat, among the rocks, and concluded he must have been more agreeably employed than in throwing his dagger, for the prospect is most charming.’

William Hutton, ‘Remarks Upon North Wales’ (1803)

An amusing aside, perhaps, but the view from Pen y pigyn is really rather charming, it must be said.

Owain Glyndŵr’s dagger - possibly a 7th - 9th century mission cross.

In fact, the lintel stone has been stylistically dated to the 7th-9th century, predating the current church by several hundred years and pushing back a Christian presence here of some substance to well before the Norman Conquest. We are, in fact, in the realm of missionaries and saints. It is possible that the lintel stone is what remains of a mission cross, perhaps of some considerable height and presence, a preaching point for itinerant missionaries. Corwen, situated at the coming together of ancient routeways (5) would have been a terribly practical place to spread the Christian word.

Owain Glyndŵr’s dagger - the stone as shown in the Royal Commission's Merioneth Inventory of 1921.

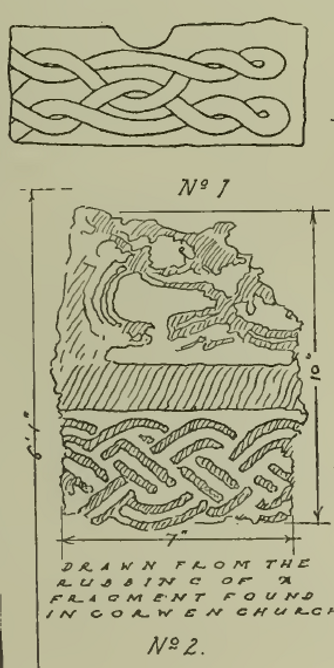

Then there is the curious loss of two pieces of carved stone, both of which would seem to predate the current 12th century church.

‘At the time of my visit to Corwen in 1835, I also found an oblong stone lying at the base of the font, having on the upper surface a double interlaced ribbon pattern with a semicircular impression on one of its larger sides.’

J. O. Westwwod, Lapidarium Walliae, (1876-1879), p.168

By the time of the Royal Commission’s visit at the beginning of the 20th century, Westwood’s find had been lost. However, based on the drawing in Lapidarium Walliae, it has been dated to the 9th-11th century. And though Westwood’s stone had been lost, the visiting inspector of the Royal Commission did find a second stone which seems to have been unearthed during the restoration of the west tower in 1907. This too was subsequently lost, despite a search by the vicar of the yards of various builders merchants in the town. The inspecting officer at the time of the find did take a rubbing, which is now the only remaining evidence of the stone’s existence. An examination of the rubbing would suggest that it was of a different geology to the existing cross shaft in the churchyard, and was perhaps part of Westwood’s lost cross. It is even possible that it was a separate cross entirely, and what we have then is a site that owned two maybe three crosses of varying antiquity - of which the remaining fabulous shaft to the south west is actually the most recent.

The lost stones of St Mael & St Sulien's - evidence of a second, perhaps third cross within the churchyard. From the Royal Commission's Merioneth Inventory of 1921.

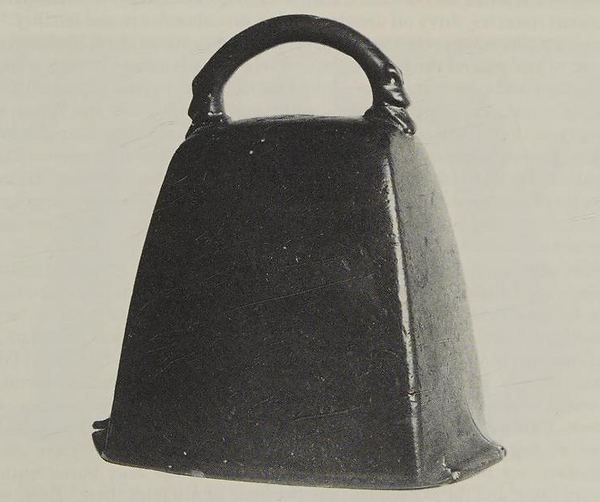

There is also the matter of a lost medieval bronze bell, said to have been found at Kraig Korwen, or more specifically at Ffynnon-y-gloch-felen (Well of the yellow bell), which rises a little ways up the hill on the way to Pen y pigyn. Such bells were used as part of the liturgy and were often attributed to a specific saint and to hold considerable power - certainly if Gerald of Wales, writing of his travels in Wales in 1188, is to be believed.

‘The common people, and the clergy, too, not only in Ireland and Scotland, but also in Wales, have such a reverence for portable bells, staffs crooked at the top and encased in gold, silver or bronze, and other similar relics of the saints, that they are more afraid of swearing oaths upon them and then breaking their word than they are the Gospels. The reason is that, from some occult power with which they are gifted as if by God, and from the vengeance of the particular saint in whose sight they are particularly pleasing, those who scorn them are punished severely, and those who break their word live to rue the day.’

Gerald of Wales, The Journey Through Wales, Thorpe, p.87

The Llangwnnadl Bell, now kept in the National Museum. Corwen's Yellow Bell would have looked very similar.

Existing examples of medieval hand bells are now extremely rare,(6) and it is curious that another was said to have been found at Cwm, some 28 miles north of Corwen and where the church there also shares a dedication to the saints Mael and Sulien.(7) There was also found near Corwen, what has been described as a ‘medieval thurible’, a censer. Such finds, though now lost, do lend tremendous weight to the importance of the church here at Corwen.

The church itself has been much restored over the last 900 years or so, as you would expect. The original cruciform plan of the church - nave, chancel, north and south transepts was added to sometime in the 14th century with the building of the west tower. The three lancet windows in the east wall above the altar are thought to be contemporary with the original build, though the stained glass is a much later addition. An early medieval survival in the church is the font, probably 12th century and contemporary to the original raising of the church here, with its simple cable moulding at the base.

The 12th century font with the tell-tale cable moulding.

One of the wonders of the church is the semi-effigy of Iorwerth Sulien, Vicar of Corwen, which can be found recumbent beside the altar. Gresham has dated it on stylistic grounds to the mid 14th century (1340-1350). Given its age, it remains in good repair. It shows the priest in Eucharistic vestments, holding what would appear to be a communion cup. Some 6ft in length, it tapers gently to the feet which rest upon an unknown animal. It was possibly unfinished, given the difference in apparent quality from the figure in high relief at the head of the effigy to the rough and ready base. It is, of course, possible that the base has suffered a greater amount of damage over the years. The inscription is bold and clear in florid, well cut Lombardic capitals.

HIC IACET IORWERTH SULIEN VICARIUS DE CORUAEN ORAPROEO

Here lies Iorwerth Sulien, Vicar of Corwen, Pray for him

The effigy may have been intended to be free standing. Nothing at all is known of Iorwerth, (8) who seems to have taken the patrimonial name of Sulien. However, it’s a pleasant whimsy to think of Iorwerth being responsible for the building of the west tower, if only because we can place him in the same century as its raising.

Here lies Iorwerth Sulien...

There seems to have been little further change to the fabric of the church until the 18th century when the north porch was added. It was at this time that the quite breathtaking, blatantly prehistoric monolith was built into its east facing front. This stone named, ‘Carreg y big yn y fach Rewlyd’(9) was said to have stood within what became the churchyard here. Any attempt to build the church in any other place was doomed to failure. Such legend is legion, of course, and can be found scattered about these Islands, including at nearby Llangar. But consider the presence here of this prehistoric stone, the attempt of myth and legend to explain its presence. It speaks volumes of the significance of this place, stretching millenia through time. For there to have been a standing stone here tells of its ancient importance - an importance that stayed vibrant through the ages, through the changes in culture, religion and the fabric of society. It could have stood within the churchyard for centuries before the building of the 12th century clas. You can imagine the early Christian missionaries arriving here, in this spot many hundreds of years ago, looking upon the stone and considering its significance - much as we do today, in fact.(10) Did they think to adapt its obvious, ancient importance to this new faith they carried? Did they simply respect the significance of the place in which it stood? Whatever the motivation, it remained and still remains as part of the fabric of this sacred spot.

Built into the north porch, the prehistoric Carreg y Big yn y fach Rewlyd, 'the pointed stone in the icy nook', is a reminder that Corwen is far older than its Christian past.

The church was further heavily restored and added to in the 19th century, during that great Victorian paroxysm of church change and renovation. A south aisle was added to the church and the south transept removed, while vestries to both the west and east were added. The top stage of the west tower was restored in 1907 with the resetting of the old windows on new sills - the date is recorded on the lintel of the north facing doorway of the tower.

The interior of the church is also well worth a wander. The oaken chest is possibly medieval while the nave ceiling is of six bays and 17th century in date, with tie beams resting on corbels and boasting queens-post collars. The altar rails may well be fashioned from the wood of the older roof. The remaining north transept is now the Lady Chapel and full of character. There are many fine memorials within the church, as you might expect from such a large parish, and several stand out, for their age or their size and extravagance. The wonderful memorial to Captain Hans Blake is of the latter. The memorial has an exact copy at St Matthew’s Windsor Anglican Church in Sydney, Australia, the birthplace of Blake’s wife, Henrietta. The couple lived with their three children at Glanalwen, a farmstead between Corwen and Cynwyd on the west bank of the Dee - curiously, not that far from the tiny village of Druid,(11) a little further down the A5, which was also the name of his last command, HMS Druid. Blake had spent much of his life in the Royal Navy, fighting in Britain’s many colonial endeavours, but succumbed to, ‘a violent African fever’ in January 1874. Why they chose to live at Corwen is not known, since there doesn’t seem to have been any familial connection. But with a life spent in warfare, one cannot think of many other better places to calm a shattered and wearied spirit.(12)

The memorial to Captain Hans Blake - who lived with his wife and children at nearby Glanalwen.

The churchyard is full of wonder. The quite glorious churchyard cross is discussed elsewhere, but there is more. Pause at the kneeling stones, as many have done before you, not far on the left from the lych gate as you enter the churchyard from the north. Thought to date from the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, they are likely a fairly local tradition, since there are others at Llangar and Gwyddelwern. Elias Owen describes them as, ‘touchingly simple in their construction’, possibly rendered without the graft of a mason, and cut to allow friends and family to mourn their loved ones. Thomas Pennant elaborated on this a little, writing,

‘In some places it was customary for the friends of the dead to kneel and say the Lord’s Prayer over the grave for several Sundays after the internment, and then to dress the grave with flowers.’

Thomas Pennant, ‘A Tour in Wales’ Vol II (1796)

The 'touchingly simple' kneeling stones.

Opposite to the kneeling stones on the right of the lychgate is a curious cross base of three stones. The oaken stump is from the early 19th century, but the steps themselves may well be early medieval and have a connection to the lost stones discussed earlier.

The curious cross steps - evidence of one of the earlier medieval crosses?

Behind the Church is the rather lovely Coleg y Croes, commissioned in 1709 as almshouses for the widows of the clergy, in the will of William Eyton of Plas Warren in Shropshire, no doubt a relation to the vicar of Corwen at the time, Kenric Eyton. The almshouses became homes in the 1930s, before being reborn as a centre for Christian retreat in around 1985, and since 2018 they have been holiday cottages. The inscription above the entrance reads,

‘Corwen College

For six widows of clergymen of the Church of England who died possessed of cure of souls, in the county of Merioneth

Built and endowed A.D. MDCCL by the legacy of William Eyton, Esq of Plas Warren, Shropshire 1750’

Coleg y Groes.

But no wander around the churchyard would be complete without a visit to the grave of the wonderfully named, Owen Owen, Engine Driver, upon whose grave is written,

His last drive is over, death has put on the break

His soul has been signalled, its long journey to take

When death sounds the whistle the steam of life fails

And his mortal clay shunted till the last trumpet calls.

St Mael and St Sulien’s is quite the most wonderful church and churchyard, so full of wonder that one could quite lose an afternoon simply wandering amongst its beauty. And when you do visit, know that you stand in a place of the greatest antiquity.

Footnotes

1. There are perhaps others, while some here could be considered a little controversial. Ho hum.

2. History of the Diocese of St Asaph (1874), p.686

3. Baring-Gould and Fisher also make the claim that Guto’r Glyn in an elegy to the parson of Corwen, Sir Benet, makes mention of Sulien and Mael in the same breath, but alas I have only been able to read of Sulien in his works.

4. Sometimes known as Bardsey Island, located off the Llŷn Peninsula.

5. Corwen’s geographical convenience is so self evident that it is hard not to draw the conclusion that its history has been largely dictated to by its situation. From ancient standing stones and the siting of Caer Drewyn, to its importance as a coaching town on Telford’s Holyhead Road (now the A5), Corwen has always, it seems, been something of a place of gathering and meeting.

6. Curiously, while the majority of existing medieval hand bells are to be found in Ireland, current thinking would suggest that the art of handbell making may well have originated in Wales and spread throughout the British Isles.

7. It will probably come as no surprise to find that there is a heavy weight of ongoing debate regarding the importance of handbells in the early medieval period. Suffice at this stage to say, that the description of the bells as yellow can be taken to mean that the bell was ‘brazen’ or bronzed, which indicates a ‘baptised’ bell, and one used for liturgical purposes. An ‘unbaptised’ bell, one of simple iron, was probably used for more pragmatic purposes.

8. The earliest recorded vicar of St Mael and St Sulien’s seems to be of a John Toone in 1533.

9. ‘The pointed stone in the icy nook’. See also Carreg y big above nearby Llangollen.

10. It is possible, of course, that the stone was moved from elsewhere, but if so…why?

11. Still, it must be said the name would seem to be an anglicisation of Y Ddwyryd - two fords.

12. The North East Wales Archives Blog.

Further Reading

V. E. Nash-Williams, The Early Christian Monuments of Wales, Cardiff, (1950)

E. Owen, Old Stone Crosses of the Vale of Clwyd, Oswestry & Wrexham, (1886

T. Pennant, Tours in Wales, Vol. II, (1781) ed. J. Rhys, (1883)

ed. J. Beverley Smith & Llinos Beverley Smith, History of Merioneth Vol. II, The Middle Ages, Cardiff, (2001)

RCAHM, An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, Merioneth, London, (1921)

D. R. Thomas, A History of the Diocese of St Asaph, London, (1874)

J. O. Westwood, Lapidarium Walliae, The Early Inscribed and Sculptured Stones of Wales, Oxford, (1876-1879)