‘This has been much mutilated, probably by the commissioners appointed in Elizabeth’s reign to destroy crosses, roods, copes, etc; but that it was saved at all, would seem to indicate a degree of favour.’

M. H. Lee, Archaeologia Cambrensis, (1876), p.208

In order to save the splendid churchyard cross in the grounds of St Chad’s in Hanmer from the threatened mallet of the iconoclasts, it was said by some to have been removed to safety. It is difficult to establish the truth of this tradition. In his visit to Hanmer in 1684, the Duke of Beaufort makes no mention of a cross at St Chad’s - and he was apt to do so, especially since the survival of such an overtly religious monument would have been something of a surprise. There is a church record of 1739 of a sum of 10s 2d paid, ‘for setting ye cross straight’. It may be that this sum was the price of having the cross reinstated in the churchyard, though of course it may simply record the repair and re-erecting of the thrown down cross, laying in pieces in the churchyard. While a standing churchyard cross with its tabernacle intact would have been worth mentioning, it's likely that Beaufort had seen so many broken churchyard crosses by the time he arrived in Hanmer that another shattered and broken shaft was neither here nor there. And it must be said that the damage to the crosshead is substantial and almost certainly not the sole responsibility of time and weather, despite Lord Hanmer’s belief, writing in 1877, that the cross was, ‘to no one a stone of offense’.

Writing in 1876, the vicar of St Chad’s, M. H. Lee (1) was of the mind that the cross had been heavily mutilated by the Elizabethan Commissioners, and in this he may be right. The crosshead is indeed badly worn - the detail virtually illegible. We are dependent on the various drawings and interpretations of academics, antiquarians and indeed, vicars from the 19th century to interpret the faces of the existing crosshead with anything more than guesswork.

The best preserved face is that facing north. The figure of what is certainly a bishop is sure enough, and both Thomas and Lee suggested that this may well be St Chad himself, though that can only be speculation. The bishop is habited and holds a crozier and what Lee took to be a psalter or perhaps a book of prayer. Beneath the bishop is the remains of an angel, now almost entirely worn away. Beneath the angel, according to Lee’s drawing was what once was a shield bearing what was thought to be two lions passant, the arms of the Lestranges. Lee took this to give credence to an early 14th century date of the cross in the churchyard,(2) which he felt was further supported by a somewhat obscure reference of Griffith Hiraethog to, ‘a stone by the noryd in the wal of the Ch’he in text hand Upton the Stone Kros.’(3) This rather baffling bit of baffle is seen by some, Lee included as referencing John de Upton, otherwise known as Goch Gwtta,(4) vicar of St Chad’s at the beginning of the 14th century, and alluding to his being responsible for the churchyard cross.

The north face of the cross ~ Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1876

The remaining faces are in a far worse state, and we must lean on Lee for much of what we know.(5) The south face of the crosshead also displays a bishop, holding a large mitre. The damage is extensive, but Lee states that the figure had his left hand raised in a benediction, though that hand has now been eroded away. Thomas was of the opinion that this figure may well have been St Dunawd, the abbot and founder of the monastery at Bangor-is-y-coed, (6) but Lee was less keen. There was, as on the north face, the figure of an angel beneath.

The south face of the cross ~ together with the illustration from Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1876 as comparison.

The east face depicts a crowned and sceptered Mary bearing Christ with two kneeling figures beside her - this we can be fairly certain of. Lee, writing in 1876, adds a demon on her right, thrusting a sword into Mary’s side while on her left the figure offers incense - this is now far less clear. Beneath is the winged head of a demon with ears like a cat with a flood of water erupting from its mouth. Interestingly, there would seem to be a squarish hole above the figures, which may at some time have supported a lantern attached to the cross.

The east face of the cross ~ together with the illustration from Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1876 as comparison.

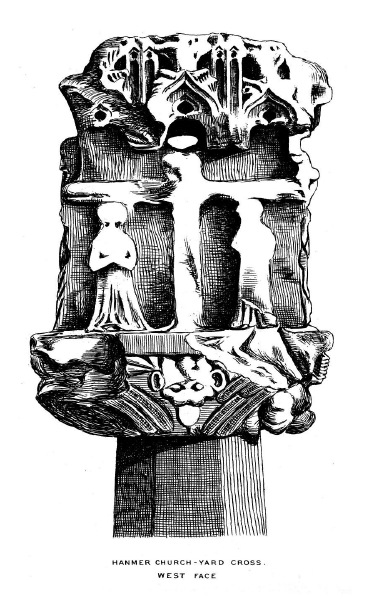

The west face is by far the most mutilated - by time, the elements and, as likely as not, the mallet of the iconoclast. The subject is traditional - that of a Crucified Christ flanked with the figures of Mary and John, and was probably the particular object of the ire of the commissioners. Today, the shadow of the chest and outstretched arm of Christ is all that is discernible, though beneath his feet the image of the head of a demon with a loudly proffered tongue is still clear enough.

The west face of the cross ~ together with the illustration from Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1876 as comparison.

The first two steps of the cross are original, but there is some debate as to the next - probably dating to the middle of the 19th century. The octagonal socket stone is definitely modern. The slender, unadorned octagonal and chamfered shaft is near enough an impressive 3m in height, supporting the much worn crosshead. As mentioned earlier, it has been dated to the early 14th century, largely on the grounds of its association with John de Upton and the Lestrange family. Stylistically, there is nothing that would assertively gainsay such a conclusion.

The Hanmer Churchyard Cross is one of only a few examples in Clwyd that retains its crosshead - mutilated though it is. It is in rare company - that of Derwen, Trelawnyd and Tremeirchion and something of a Clwydian outlier. It’s not like you need an excuse to visit Hanmer, but should you find yourself debating a visit for some reason, the cross should sway you yay.

Footnotes

1. M. H. Lee was the vicar of St Chad’s from 1867 and in the fire of 1889, rather heroically managed to break through a window into the church in order to save the registers. He died in 1890 at the age of 58, probably from injuries he suffered in doing so.

2. Lee supposes the shield is a reference to the time at the beginning of the 14th century when the Lestranges held St Chad’s in opposition to its ownership by Haughmond Abbey.

3. Hengwrt MSS Peniarth 428

4. This has been translated as, ‘Red and Short’, but may in fact relate to his clothing - a red mantle.

5. A degree of care must be taken in accepting Lee’s interpretations, but there is evidence that he questions himself, which is encouraging, and one must be aware that as vicar of St Chad’s he was in an excellent position to both study the cross and absorb the knowledge of those local that knew it intimately.

6. Bangor on Dee, Wrexham County.

Further Reading

H. Burnham, A Guide to Ancient and Historic Wales: Clwyd and Powys, HMSO, (1995)

J. Lord Hanmer, A Memorial of the Parish and Family of Hanmer in Flintshire, London, (1877)

M. H. Lee, Calvary Cross in Hanmer Churchyard, Archaeologia Cambrensis, (July 1876)

E. Owen, Old Stone Crosses of the Vale of Clwyd, Oswestry & Wrexham, (1886)

R. J. Silvester & R. Hankinson, Medieval Crosses and Crossheads, CPAT Report No. 1036, (March 2010)

D. R. Thomas, A History of the Diocese of St Asaph, London, (1874)

An Account of the Official Progress of His Grace, Henry the First Duke of Beaufort Through Wales in 1684, London, (1883)