You have an idea, I imagine, of how a church should look - there’s a sort of image in your mind’s eye, I should think, by which all churches you visit are measured. Quite right. For me, less is more. Don’t misunderstand me, I’m as fond of a cathedral as anyone, towering massives, spires and towers stretching heavenward, strain reaching to God. But, for me, St Mary Magdalene’s in the ancient village of Gwaenysgor is all that a church should be. Squat, compact and simple, at the centre of all things within its community, and so achingly beautiful that one would do well not to swoon.

‘In Carn-y-chain and Gwaenysgor there is land for 1 plough, and there is [1 plough] in demesne, with 2 Frenchmen and 2 villans, and 1 waste church. It is worth 15s.’

Domesday Book, A Complete Translation, (1992), p.737

By the time the Normans arrived in the later 11th century, the church here, which perhaps had been raised several hundred years earlier, was derelict and in ruin. It was possibly the site of an early Celtic church, a llan, since there are signs that the present church might well be within a circular enclosure. Some have suggested a Saxon origin, and such a thing is possible, if not entirely probable given the fluid and flux nature of the politics of the area in the years before the Norman arrival.

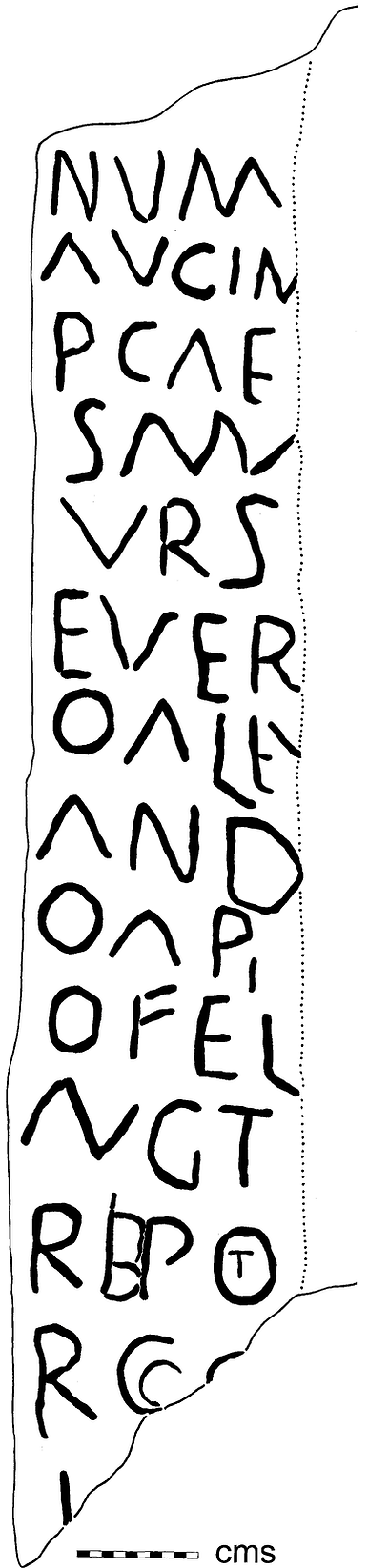

The discovery of a Roman milestone in 1931 during repair work on the churchyard wall might, on the face of things, indicate a Roman settlement here. But it would seem that the milestone was removed to Gwaenysgor to serve as building material from the Roman road some 6km further south, connecting the towns of Deva, Varis, Kanovium and Segontium.

Still, this should not take away from the importance of the milestone in any way - there are only a little over a hundred milestones in the UK. It was reburied soon after its discovery when the inscription was recognised, and found once again in 1956 when work on demolishing a series of cottages by the churchyard was undertaken. Apparently its survival was somewhat fortunate, since on both occasions, the stone was close to being entirely broken up for building work. It has suffered some damage, the right edge having been lost due to chamfering, probably in 1931 when it was likely being dressed for modern use. The Latin renders into English as,

To the Divinity of the Emperor, for the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander Pius Felix Augustus, with tribunician power, proconsul, father of his country.

NVM

AVG IM

P CAE

S M A

VR S

EVER

O ALEX

AND[.]

O A PI

O FEL

A͡VG T

RI͡B PO͡T[.]

RỌ͡CỌ[.]

P̣ […]

Interestingly, it is one of only two milestones found with an inscription dedicated to numen Augusti, the other found on the same Deva to Segontium road in Ty Coch, near Pentir south of Bangor. Its present whereabouts are unknown. It was last thought to be in the possession of T. T. Pennant-Williams at his home in Rhyl at the end of the 1960s, but has now been lost, despite suggestions that it is somewhere in the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff.

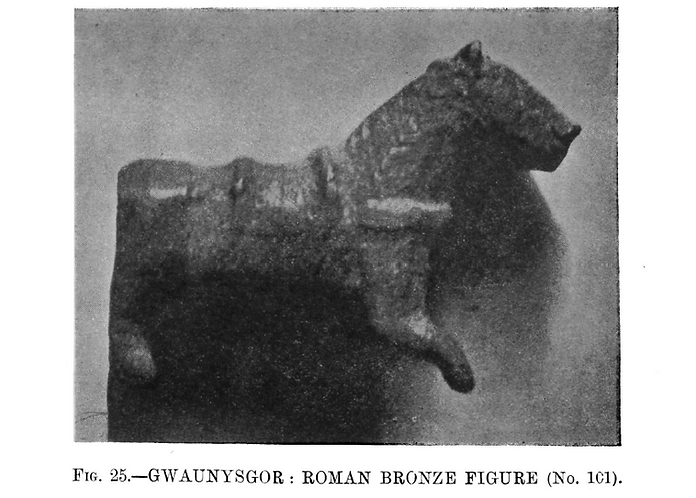

The Romano-British bronze horse figurine, found in 1875 - RCAHMC, Flint, 1912

However, if the milestone does not necessarily suggest that Gwaenysgor was a centre of Roman activity, the find in 1875 of a small bronze horse figurine does point to the area being of some importance to the Romans. It was found in the soil of a freshly made grave in the churchyard, and has been described as ‘unquestionably of Roman craftsmanship’, though it is possible that it could be of Romano-British origin. It is hollow and was originally riveted to a separate object, probably, according to the Royal Commision, a horse's harness or the military dress of a cavalryman.

The figurine is one of those ancient artefacts that seem to whisper to you from a great distance - saying something of tremendous value if only you could hear clearly. It is easy to misunderstand such whispers, easy to hear what you wish to hear - one must be careful, cautious. I have a wonder, you see, as to the possible existence of a horse cult in the Vale of Clwyd - such veneration was not uncommon in Celtic culture. Perhaps here, perhaps at Gwaenysgor we have a little evidence. But then again, perhaps this is wishful thinking. A point for another time…

The Domesday Book of 1086 makes clear that the church at Gwaenysgor was ruinous. Why this was so is a bit of a mystery, but given the near constant regional warfare between the native Welsh and the Saxons, it is perhaps not entirely surprising. It is possible, of course, that it was destroyed in the years following the arrival of the Normans in north Wales, before the compilation of the Domesday Book. The church was rebuilt and likely rededicated by the Normans - St Mary is something of a giveaway. Any previous dedication is completely unknown. The church returns to recorded history in the Norwich and Lincoln Taxations of 1254 and 1291, respectively, though there is nothing remaining of the 13th century church, save the font.

The 13th century Norman font - the shafts renewed, but the bowl is original. A replica of...

...the font within Lincoln Cathedral.

This astonishing work is a replica of the font currently within Lincoln Cathedral and has been dated to the early 13th century, predating the later Taxations. A thick central shaft surrounded by four smaller shafts, probably renewed, support a doubtless ancient bowl decorated with foliage and the image of a human head. A sturdy, imposing thing of rugged beauty.

On entering the church, two things will strike you immediately. The porch is unusually large - seemingly far too big for a church of this size. But here we have evidence of a church as the centre of its community. It was likely that the porch was used by the parishioners for meetings and gatherings, a place to make decisions for the community. It has been dated to the late 15th or early 16th centuries, and has stone benching on either side. There is also the matter of the rather wonderful arch that faces you as you enter, the arch that you must pass beneath to enter the church. It is thought to be unique, such a piece of work unheard of elsewhere in the British Isles. Spanning the width of the entrance, the wooden arch is constructed of two unchamfered vertical timbers which continue to form an arch at the apex. A later three piece collar has been added above the arch, attaching the whole to the porch entrance.

‘Within this porch is a curious doorway, of very wild character, and perhaps early.’

S. Glynne, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1884, p.86

The astonishing arch - 'a curious doorway, of very wild character.'

The arch is decorated with Christian symbols upon the spandrels - on the right is a bird, possibly a peacock, an early Christian symbol for the Resurrection. There are Greek crosses on both sides and foliage, flowers and an odd series of circles within a triangle. All have been gouged from the wood, and the overall sense of the arch is that this is the work of local craftsmen, an object of community devotion incorporated into a church that was entirely at the centre of village life. Despite suggestions that the arch is very early, it has been dated to the 16th century, and is possibly contemporary to the building of the porch. There are suggestions that the arch was plastered over until uncovered by the restoration of 1931, but given that it was described by the Royal Commission in 1912 (after a visit in 1910), this seems unlikely. However, the arch and its carvings are not mentioned by Thomas in his History of the Diocese of St Asaph, dated 1874, and one could reasonably have expected him to do so had the arch been unencumbered by plaster. It would seem then, that the arch was cleared of render sometime at the end of the 19th century, unless of course it was hidden in the 20 years between the Royal Commission’s visit and Hughes’ restoration, which seems unlikely.

A single celled wonder - looking towards the chancel, the rood screen long since removed. Note the chairs - no pews here.

At its core, the church is medieval, but has, as you would expect, received much attention in the many years following, with a series of repairs and restorations. It is a wonderful single celled affair, a simple chamber of real beauty. Thomas states that a rood screen once separated the nave and chancel, but this seems to have been removed possibly around 1845, during one of the several restorations of the 19th century. During services, women were said to have been seated in the nave of the church, while men worshipped in the chancel. Rather beautifully, the parishioners were required to bring their own chairs to services, taking them home afterwards. It's hard not to think of this when in the nave or in the churchyard, looking at the line of chairs against the south wall.

The roof, which was boarded up until the restoration of 1931, is a beautiful arched-braced affair - described as a ‘close-couple type’ and dated to the 15th century. It has been said that it was installed when the original thatched roof of the church was replaced with much heavier slate. It remains a wonder that such beauty is often hidden from view, but probably reflects the condition that many of these wooden wonders find themselves, before renovation.

In the north wall you will find the remains of the ‘Devil’s Door’ - blocked and with a small window installed. It is possible to see the remains of the hinges if one looks carefully enough. Such doors remain a source of legend - wonderfully so. They were said to have been left open during baptisms to allow the evil expelled from the infant child to flee. It is probably for this reason that many of them were blocked up and sealed after the Reformation and the religious convulsions of the 17th century.

Largely hidden behind a variety of stored debris - the blocked 'Devil's Door' in the north wall.

During the restoration of 1931, the much battered remains of frescos were discovered on the walls, ‘hacked to receive the nineteenth century finishing plaster’. One of these was believed to be an image of a red fish, leading Hughes at the time to suppose it was part of a larger St Christopher, which were traditionally placed on the north wall before the entrance, in order to reassure arriving parishioners against sudden death, fainting and falling. Perhaps the most famous wall painting of St Christopher can still be seen in all its glory at St Saeran’s at Llanynys.

There are a number of sepulchral slabs within the church. Many have been recovered from their use as lintels and supports, of one form or another. Attached to the north wall of the chancel is a splendid slab, rescued from its use as a lintel above the entrance. At the head of the slab are four circles with a three lobed leaf in each, a flower, or perhaps a wheel at their centre, all contained within a ring band. This is set upon a shaft, an ornamental knop close to the top, set upon what has been described as a, ‘simple calvary’. Hughes describes a small triangle cut into one of the steps, which he suggests may have been created to symbolise the hilltop upon which the Crucifixion took place - it remains unclear. The sword to the right of the shaft is impressive - with its rounded pommel stretching down for much of the length of the shaft. Beside the slab are the remains of another, much smaller sepulchral slab.

The sepulchral slab afixed to the north wall of the chancel - perhaps 13th century.

In the south wall of the nave, the window has the remains of a sepulchral slab used as a sill. It is not in form dissimilar to the larger example in the north wall of the chancel. It consists of a small cross in the centre of a larger cross head within a circle, with a shaft leading down from the head. It is hard not to suppose that though lost, the shaft base ended in a calvary, just as the example in the chancel, especially since this also has a sword with a rounded pommel to its immediate right. Sepulchral slabs are difficult to date, but St Mary’s have been variously assigned to the 13th and 14th centuries - which of course is a rather large period of time, so one would suppose we are fairly safe to accept the range.

Within the chancel, the small engraved oaken altar is of some considerable interest. It is dedicated to John Owen, Bishop of St Asaph between 1629 and its abolishment in 1646 by the Commonwealth at the end of the First English Civil War. Owen was favoured by the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud and liked by Charles I, becoming chaplain to the King. He was elevated to the bishopric of St Asaph as a result of this powerful support. His favouring of the monarchy during the Civil War was his downfall, and he spent some time imprisoned in the Tower of London having been accused of treason. He died in 1651 and was buried in St Asaph Cathedral.

The churchyard shows some signs of having been circular, and as has been said, this might well indicate a Celtic origin to the church - pre Saxon and Norman. The find of the Romano-British horse figurine is intriguing. There is a sundial to the south west of the porch, and Glynne supposed that this was possibly the remains of the churchyard cross - which is entirely possible.

The Church of St Mary Magdalene’s in Gwaenysgor is nothing short of a salve to the soul. It is, as you would imagine a church in a small community should be - at the centre of all things. It has the most complete Parish registers of anywhere in Wales, dating back to the order to collect them in the mid-16th century. Simple and beautiful, uncluttered and wondrous, it is quite the most wonderful of places. Visit - you won’t regret it.

Further Reading

CPAT, Flintshire Churches Survey, Church of St Mary Magdalene, Gwaenysgor

F. H. Crossley & M. H. Ridgway, Screens, Lofts And Stalls Situated In Wales and Monmouthshire Part 2, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1945

E. Davies, The Prehistoric and Roman Remains of Flintshire, Cardiff, 1949

E. Hubbard, The Buildings of Wales, Clwyd, Penguin, London, 1986

H. H. Hughes, Church of St Mary Magdalene, Gwaunysgor, Flintshire, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1932

S. Glynne, Notes on Older Churches, Archaeologia Cambrensis, April 1884

E. Owen, Gawunysgor Church Partial Restoration, Archaeologia Cambrenis, October 1892

RCAHMC, An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire: County of Flint, London, 1912

E. E. Pridgeon, Saint Christopher Wall Paintings in English and Welsh Churches c. 1250 - c. 1500, University of Leicester, 2008

D. R. Thomas, Archaeologia Cambrensis, July 1876

D. R. Thomas, A History of the Diocese of St Asaph, London, (1874)

ed. A. Williams, G. H. Martin, Domesday Book A Complete Translation, Penguin, London, (1992)